1. The movie treats the subject of modern flight as kitsch, such as we see in the close-up shots of Clooney swiveling his rollerbag, sliding his card through the check-in kiosk, going through security with a straight face, etc. The vulgar aesthetics of air travel draw chuckles from a knowing crowd. It is curious that Clooney's character, the exit strategist Ryan Bingham, is held up as someone who reflects the autonomous fantasy of taste (we see him shopping for ties at an airport clothiers, and we note that he has those flexible Nike shoes packed in his bag), and is shown to have his taste entirely defined for him by the whims of airline protocols, airport consumer culture, and corporate rewards programs. The monotonous airport scenes function as an analog to the predictability of the total system at hand—the human becomes passive and numb, an agent of nothing—but still moving at impressive speed. For kitsch to work, we all have to know things are ugly, and then buy them anyway. Imagine the feeling of gratification that passengers will have when they are able to enjoy their kitsch surroundings while also seeing this movie as in-flight entertainment: a circle will be complete, but nothing remarkable will have happened.

2. Flight is also depicted as earnest Romantic material, thus the impossible aerial views (views such as no window seat ever actually affords); the wish image of infinite destinations that appears when Clooney looks up at sprawling departures screens and his eyes flick back and forth; and in the metaphor of "connection" that is at turns lampooned and honored throughout the film. Air travel still maintains the slightest residues of the Romantic, and UP IN THE AIR provides ample examples of how just residual these impulses really are: We know that flying in a commercial airliner does not deliver the god's eye view, and yet we accept the cinematic conceit. We know that flight schedules are anything but unlimited matrices of potential new geographies, and yet the informational screens of arrivals and departures still manage to convey some remnant of discovery. Finally, without kisses at the departure gate, or hugs the moment one steps out of the jet-bridge, and with the airport police keeping you from leaving your car at curbside, we know that airports are no longer the place for sustained emotional 'connections'...and yet, we say sure, we'll watch a movie that tries to keep alive the myths and promises of making a 'connection' in flight.

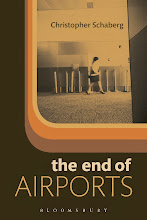

On this last note, what is it about airports that lend themselves to excessive metaphor? Let us be clear, the idea of "connection" is strictly metaphorical here; come to think of it, I do not recall a single scene in the film in which Clooney actually makes a 'connection'— all his flights appear to be direct flights. The 'connection' in this movie is derived from the energy and aura of airports, but it really takes root in an over-fertilized soil of Hollywood romance mixed with Midwestern sentimentality. But in a general sense, this metaphorical excess is an airport problem. Consider one poster for the film:

Look at the layers of metaphor in this image. The "connection," as I've insisted, is not about the airport. This image is a riff on the scene in which Clooney and his understudy are departing Detroit; they are at the beginning on their trip, not in a 'connecting' airport. "Arriving this December" is a further metaphor, taking airport verbiage ('arrivals') and repurposing it as a marketing campaign for the film. The movie's title is itself a metaphor: the characters are quite obviously on the ground, and 90% of the film occurs there, too. The air facilitates the drama, certainly, but strictly speaking, being up in the air is a metaphor. The singular Boeing 747 in the mid-ground is more of a metonymy for all the American Airlines MD-80s that arc across the screen. Finally, the little bird in the upper right-hand corner of the frame is a cute but utterly unnecessary metaphor. We're in an airport, staring at a jumbo jet; do we really need a little bird to remind us that we are in the atmosphere of flight?

The overdetermined metaphoricity of airports creates a squishy subject, an absorbent material base for narratives—and this is perhaps why the kitsch surfaces and the Romantic residues of airports can be sustained together. In airports, displacement is the rule, everything stands for something else, and conflicting feelings are subsumed in the ether of progress.